By Michelle Hill, QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute, Brisbane Australia

Swapping shovels and brushes for mass spectrometers and proteomics knowledge, Prof Paul Haynes and Dr Caroline Solazzo are using ancient proteomics to reveal new understanding of human cultural heritage.

With a background in chemistry and a research program on food and environmental proteomics, Prof Paul Haynes journeyed into ancient proteomics with his Macquarie University (Australia) colleague Egyptologist Dr Jana Jones as well as Dr Raffaella Bianucci (University of Turin, Italy).

Archaeological material is highly valuable, and Bianucci had the first challenge to obtain permission to use even a small sample from precious Egyptian mummies for proteomics analysis. Having obtained permission to collect loose skin samples from 4,200-year old mummies originating from ancient Middle Egypt, the researchers were blown away by the proteomics results. In addition to the expected collagen proteins, which are known in the field as “Survivor proteins”, proteomics provided rare molecular insight into the medical histories of two of the mummies – the proteins identified suggest the individuals might have died from cancer and lung infection, respectively. This study was published in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A.

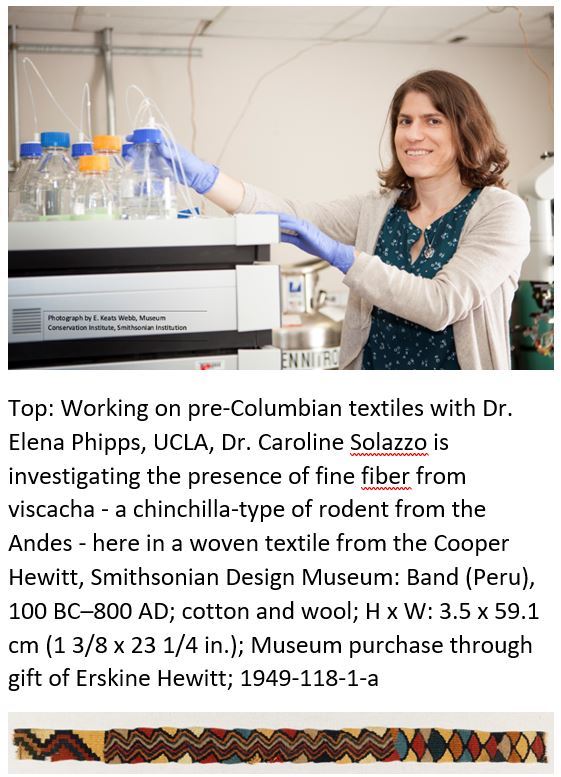

At the Smithsonian Museum Conservation Institute, Dr Caroline Solazzo has been using proteomics to identify animal tissues in historical and archaeological textiles, to better understand the techniques of production of these cultural heritage artefacts.

Solazzo used proteomics to confirm the use of dog fiber in Coast Salish blankets. The Coast Salish peoples are indigenous to the Pacific Northwest coastal areas of northern Washington and southern British Columbia, notable for large, finely woven blankets. The rich Salish oral history alludes to the use of dog hair was used as a weaving fiber, but the importance of dog fiber was questioned. Solazzo used proteomics to identify dog fiber in 19 textile samples, thus proving the oral tradition. Further, based on her finding that dog fibers were always weaved with other fibers such as mountain goat hair, more detailed information can be provided in museums.

An even more challenging question was the differentiation of sheep and goat wool in textiles used to wrap burial objects, due to their similarity, and degradation state of the buried ancient samples. Solazzo used peptide mass fingerprinting to analyse the wool wrapping from a 10th century Viking-age grave in Britain, and from 2,000 year old Mongolian bronze burial objects.

“At the time the keratin sequences were not well known for these two species, and although the two species are very close, I was able to determine one key peptide to differentiate them. Some of these archaeological fibers were challenging because they had been mineralized so microscopy was inconclusive.” says Solazzo.

Both Solazzo and Haynes highlight non-invasive sampling of ancient, precious materials as a challenge. To this end, recent development of innovative sampling techniques, such as strip-taping, should greatly facilitate ancient proteomics. While sample degradation and modern contamination are additional technical considerations, Haynes is intrigued by recent work on the use of deamidation levels as a molecular clock to estimate the age of proteins. On this point, Solazzo observed lower deamination levels in better preserved textiles, and suggested in her Journal of Archeological Science article, that the corroding copper salts from the wrapped bronze objects acted as a biocide to help preserve the textiles.

Now hooked on mummies, Haynes and several PhD students are part of an interdisciplinary team on The Mummy Project at The University of Sydney’s Chau Chak Wing Museum. Meanwhile, Solazzo has been developing proteomics tools to identify baleen, tortoiseshell and horn, materials that are difficult to recognize and are poorly preserved in archaeological contexts, making them challenging for DNA sequencing technologies, but are of cultural significance, often being used in buttons, jewellery and furniture.

.png)